|

The cultural relations between India and China can be

traced back to very early times. There are numerous references to China in Sanskrit

texts, but their chronology is sketchy. The Mahabharata refers to China several

times, including a reference to presents brought by the Chinese at the Rajasuya

Yajna of the Pandavas; also, the Arthasastra and the Manusmriti mention China.

According to French art historian, Rene Grousset, the name China comes from "an ancient"

Sanskrit name for the regions to the east, and not, as often supposed, from the

name of the state of Ch'in," the first dynasty established by Shih Huang Ti

in 221 B.C. The Sanskrit name Cina for China could have been derived from the

small state of that name in Chan-si in the northwest of China, which flourished

in the fourth century B.C. Scholars have pointed out that the Chinese word

for lion, shih, used long before the Chin dynasty, was derived from the Sanskrit

word, simha, and that the Greek word for China, Tzinista, used by some later

writers, appears to be derivative of the Sanskrit Chinasthana. According to

Terence Duke, martial arts went from India to China. Fighting

without weapons was a specialty of the ancient Kshatriya warriors of India. Both

Arnold Toynbee and Sir L. Wooley speak of a ready made culture coming to China.

That was the Vedic culture of India.

Until recently, India and China had coexisted

peacefully for over two thousand years. This amicable relationship may have been

nurtured by the close historical and religious ties of Buddhism, introduced to

China by Indian monks at a very early stage of their respective histories,

although there are fragmentary records of contacts anterior to the introduction

of Buddhism.

Gerolamo

Emilio Gerini (1860 -1913) has said: “During the three or four

centuries, preceding the Christian era, we find Indu

(Hindu) dynasties established by adventurers, claiming descent from the

Kshatriya potentates of northern India, ruling in upper Burma, in Siam and Laos,

in Yunnan and Tonkin, and even in most parts of southeastern China." The Chinese literature of the third century is full of

geographic and mythological elements derived from India. "I see no reason to doubt," comments Arthur Waley in his book, The

Way and its Power, "that the

'holy mountain-men' (sheng-hsien) described by Lieh Tzu are Indian rishi;

and when we read in Chuang Tzu of certain Taoists who practiced movements

very similar to the asanas of Hindu yoga, it is at least a possibility

that some knowledge of the yoga technique which these rishi used had also

drifted into China."

Bhaarat:

Teacher of China

Trade & Commerce

Contributions

Bhaarat's influence on Japan

Conclusion

Articles

Bhaarat:

Teacher of China

Hinduism and Buddhism, both have had profound effect on

religious and cultural life of China. Chinese early religion was based on nature

and had many things in common with Vedic Hinduism, with a pantheon of deities.

"Never

before had China seen a religion so rich in imagery, so beautiful and

captivating in ritualism and so bold in cosmological and metaphysical

speculations. Like a poor beggar suddenly halting before a magnificent

storehouse of precious stones of dazzling brilliancy and splendor, China was

overwhelmed, baffled and overjoyed. She begged and borrowed freely from this

munificent giver. The first borrowings were chiefly from the religious life of

India, in which China's indebtedness to India can never be fully told." "Never

before had China seen a religion so rich in imagery, so beautiful and

captivating in ritualism and so bold in cosmological and metaphysical

speculations. Like a poor beggar suddenly halting before a magnificent

storehouse of precious stones of dazzling brilliancy and splendor, China was

overwhelmed, baffled and overjoyed. She begged and borrowed freely from this

munificent giver. The first borrowings were chiefly from the religious life of

India, in which China's indebtedness to India can never be fully told."

(source:

India

and World Civilization - By D. P. Singhal

p. 338).

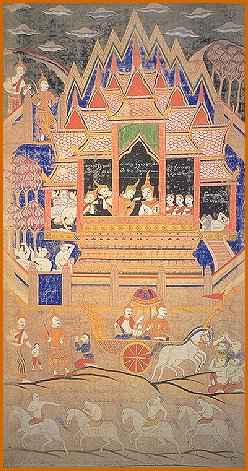

The story of Sun Hou Tzu, the Monkey King, and

Hsuan Tsang. It is a vicarious and humorous

tale, an adventure story akin to the Hindu epic

of Ramayana, and like Ramayana, a moral tale of

the finer aspects of human endeavor which come to prevail over those of a less

worthy nature. The book ends with a dedication

to India: I dedicate this work to Buddha's pure

land. May it repay the kindness of patron and preceptor, may it mitigate the

sufferings of the lost and damned....'

(source: Eastern

Wisdom - By Michael Jordan p -134-151).

Arnold

Hermann Ludwig Heeren

(1760-1842) an Egyptologist and author of Historical

researches into the politics, intercourse, and trade of the Carthaginians,

Ethiopians, and Egyptians observes that:

"the name China is of Hindu origin and came to us

from India."

"M. de Guigues says that Magadha was known

to the Chinese by the name Mo-kiato, and its capital was recognized by both its

Hindu name Kusumpura, for which the Chinese wrote Kia-so-mo-pon-lo and

Pataliputra, out of which they made Patoli-tse by translating putra, which means

son in Sanskrit, into their own corresponding word, tse. Such translation of

names has thrown a Veil of obscurity over many a name of Hindu origin. Hindu

geography has suffered a great loss."

(source: Journal of the

Royal Asiatic Society Volume. V).

Lin Yutang

(1895-1976) author

of The Wisdom of China and India:

"The contact with poets, forest saints and the

best wits of the land, the glimpse into the first awakening of Ancient India's

mind as it searched, at times childishly and naively, at times with a deep

intuition, but at all times earnestly and passionately, for the spiritual truths

and the meaning of existence - this experience must be highly stimulating to

anyone, particularly because the Hindu culture is so different and therefore so

much to offer." Not until we see the richness of the Hindu mind and its

essential spirituality can we understand India...." "The contact with poets, forest saints and the

best wits of the land, the glimpse into the first awakening of Ancient India's

mind as it searched, at times childishly and naively, at times with a deep

intuition, but at all times earnestly and passionately, for the spiritual truths

and the meaning of existence - this experience must be highly stimulating to

anyone, particularly because the Hindu culture is so different and therefore so

much to offer." Not until we see the richness of the Hindu mind and its

essential spirituality can we understand India...."

"India was China's teacher in religion and

imaginative literature, and the world's teacher in trignometry, quandratic

equations, grammar, phonetics, Arabian Nights, animal fables, chess, as well as

in philosophy, and that she inspired Boccaccio, Goethe, Herder, Schopenhauer,

Emerson, and probably also old Aesop."

(source: The

Wisdom of China and India - By Lin Yutang

p. 3-4).

Sir William Jones

(1746-1794) came to India as a judge of the Supreme Court at Calcutta. He

pioneered Sanskrit studies. His admiration for Indian thought and culture was

almost limitless. He says that the Chinese assert their Hindu origin."

(source: Annals

and Antiquities of Rajasthan; or the Central and Western Rajput States

- By James Tod Volume I, p. 35-57).

Amaury de Reincourt

(1918 - ) was

born in Orleans, France. He received his B.A. from the Sorbonne

and his M.A. from the University of Algiers. He is author of several books including The American empire and

The

Soul of India, he wrote: " The Chinese

travelers' description of life in India... reveals great admiration from all

concerned for the remarkable civilization displayed under their eyes."

"India sent missionaries, China

sending back pilgrims. It is a striking fact that in all relations between the

two civilizations, the Chinese were always the

recipient and the Indian the donor." "Indian influence prevailed

over the Chinese, and for evident reasons: an undoubted cultural superiority

owing to much greater philosophic and religious insight, and also to a far more

flexible script."

(source: The Soul of India – by

Amaury de

Riencourt p 141 and 161).

China

(Cinaratha) in the Epic of Mahabharata

It is well known that in the Mahabharata

the Cinas appear with the Kiratas among the

armies of king Bhagadatta of Pragjyotisa or Assam.

In the Sabhaparvan this king is described as surrounded by the Kiratas and the

Cinas. In the Bhismaparvan, the corps of Bhagadatta, consisting of the Kirtas

and the Cinas of yellow color, appeared like a forest of Karnikaras. It is

significant that the Kiratas represented all the people living to the east of

India in the estimation of the geographers of the Puranas. Even the dwellers of

the islands of the Eastern Archipelago were treated as Kiratas in the Epics. The

reference to their wealth of gold, silver, gems, sandal, aloewood, textiles and

fabrics clearly demonstrates their association with the regions included in

Suvarnadvipa. Thus, the connection of the Kiratas and Cinas is a sure indication

of the fact that the Indians came to know of the Chinese through the eastern

routes and considered them as an eastern people, having affinities to the Kiras,

who were the Indo-Mongoloids, inhabiting the Tibeto-Burman regions and the

Himalayan and East Indian territories, the word Kirata being a derivation from

kiranti or kirati, the name of a group of people in eastern Nepal.

Watch

Scientific

verification of Vedic knowledge

(For

more refer to chapter on Greater

India: Suvarnabhumi and Sacred

Angkor).

***

In

early Indian literature China is invariably shown to be connected with India by

a land-route across the country of the Kiratas in the mountainous regions of the

north. In the Vanaparvan of the Mahabharata the Pandava brothers are

said to have crossed the country of the Cinas in course of their trek through

the Himalayan territory north of Badri and reached the realm of the Kirata king

Subahu. The Cinas are brought into intimate relationship with the Himalayan

people (Haimavatas) in the Sabhaparvan also. The land of the Haimavatas is

undoubtedly the Himavantappadesa of the Pali texts, which has been identified

with Tibet or Nepal. In the Sasanavamsa this region is stated to be Cinarattha.

Thus, it is clear that China was known to the Indians as lying across the

Himalayas and was accordingly included in the Himalayan territories. In the Nagarjunikonda

inscription of Virapurusdatta, China (Cina) is said to be lying in the Himalayas

beyond Cilata or Kirata. These references to the proximity of China to the

Himalayan regions, inhabited by the Kiratas, show that there were regular routes

through the Tibeto-Burman territories, along which the Indians could reach

China.

Some such land-route is implied in the remark of

the Harsacarita of Banabhatta that Arjuna conquered the Hemakuta region after

passing through Cina. Of course, the route across Central Asia is

perhaps alluded to in the itinerary of Carudatta from the Indus Delta to China

across the country of the Hunas and the Khasas, described in the Vasudevakindi,

and there is probably a reference to the sea-route, passing through Vanga,

Takkola and Suvarnadvipa, in the Milindapanho. But there is no doubt that in a

large number of ancient Indian texts China is mentioned near the eastern

Himalayan regions, through which regular routes, connecting this country with

India, passed from fairly early times. It was along these routes that India came

into contact with China for the first time and developed commercial relations

with her, that are referred to by Chan K’ien in the second century B.C.

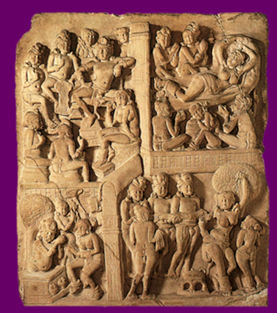

In Yunnan there is a large

number of old pagodas. Some of them are the oldest and most beautiful in China.

Their cornices and corner decoration, showing rows of pitchers (mangala ghata),

betray unmistakable Indian influence. Many bricks of these pagodas bear Sanskrit

inscriptions, containing Buddhist mantras and formulae in a script, which is

identical with that current in Nalanda and Kamarupa in the 9th

century. The beautiful bronze statue of Avalokitesvara from the pagoda of

Ch’ung Sheng Ssu near Ta-li is an index to the high standard of culture and

craftsmanship attained by the Buddhists of Yunan.

In earlier times, the people of

the east, Magadha and Videha, were in contact with Yunan, as the traditions of

Purvavideha show. The two names, Purvavideha and Gandhara, seem to represent

these two successive eastern and western streams of Indian colonial and cultural

expansion in this region.

Henry

Rudolph Davies (1865 - ) says that Besides Buddhism, Shaivism was

also popular in Yunan as is manifest from the prevalence of the cult of Mahakala

there. This ancient Indian colony in the south of China was the cradle of

Sino-Indian cultural relationship for a long time.

It

was an important outpost of Indian cultural expansion along the eastern

land-routes, which Colonel Gerolamo

Emilio Gerini (1860 -1913) author of Researches

on Ptolemy's geography of eastern Asia (further India and Indo-Malay archipelago

p. 122 -124 has described as

follows: It

was an important outpost of Indian cultural expansion along the eastern

land-routes, which Colonel Gerolamo

Emilio Gerini (1860 -1913) author of Researches

on Ptolemy's geography of eastern Asia (further India and Indo-Malay archipelago

p. 122 -124 has described as

follows:

“During the three or four

centuries, preceding the Christian era, we find Indu

(Hindu) dynasties established by adventurers, claiming descent from the

Kshatriya potentates of northern India, ruling in upper Burma, in Siam and Laos,

in Yunnan and Tonkin, and even in most parts of southeastern China.

From the Brahmaputra and Manipur to the Tonkin Gulf we can trace a continuous

string of petty states, ruled by those scion of the Kshatriya

race, using the Sanskrit or Pali language in official documents or inscriptions;

building temples and other monuments after the Indu (Hindu) style and employing

Brahmana priests for the propitiatory ceremonies, connected with the

court and state. Among such Indu (Hindu) monarchies (Theinni) in Burma, of Muang

Hang, C’hieng Rung, Muang Khwan and Dasarna (Luang P’hrah Bang) in the Lau

country; and of Agranagara (Hanoi) and Campa in Tonkin and Annan.”

“The names of peoples and

cities, recorded by Ptolemy in that region,

however few and imperfectly preserved, are sufficiently significant to prove the

presence of the Indu (Hindu) ruling and civilizing element in these countries,

undoubtedly not so barbarous as the Chinese would make them appear.”

“It is evident through the

medium of those barbarians that China received part of

her civilization through India.”

Among these colonies Tagong and

upper Pugan were called Mayura; Prome was Sriksetra; Sen-wi (Theinni) was

Sivirastra; Muang Hang, Chieng Rung and Muang Khwan were the three divisions of

Ching Rung kingdom, which the prince of Yong, named Sunandakumara, united under

Mahiyagananagara; Luang P’hrah Bang was Dasarna; Hanoi was Agranagara; Tagaung

was Brahmadesa (P’o-;o-men), where a Sanskrit inscription, dated in Gupta era

108 – 426 A.D. refers to Hastinapura, situated in that country; and, of

course, Yunana was Purvavideha or Gandhara. Thus, from Arakan, where the

Mrohaung inscriptions attest the efflorescence of Indian culture, language and

literature, to Yunnan, whose history we have traced above, Indian culture made a

triumphant advance in ancient times.

(source: Yün-nan;

the link between India and the Yangtze – by Henry Rudolph Davies

Cambridge University press 1909 an India

and The World - By Buddha Prakash p. 141-150).

India was known as

T'ien-chu to the Chinese.

***

China, like Southeast Asia too, was colonized to

some extent by the ancient Hindus. The religion and culture of China are

undoubtedly of Hindu origin. According to the Hindu theory of emigration,

Kshatriyas from India went and established colonies in China. India was known as

T'ien-chu

to the Chinese.

Colonel

James Tod (1782-1835) author of Annals

and Antiquities of Rajasthan: or the Central and Western Rajput States of India

has written:

"The genealogies of China and Tartary

declare themselves to be the descendents of "Awar," son of the Hindu

King "Pururawa."

According to the traditions noted in the Schuking,

the ancestors of the Chinese, conducted by Fohe, come to the plains of China

2,900 years before Christ, from the high mountains Land which lies to the west

of that country. This shows that the settlers into China were originally

inhabitants of Kashmir, Ladakh, Little Tibet and the Punjab, which were parts of

Ancient India.

Kakuzo

Okakura, speaking of the missionary activity of Indian Buddhists in

China, says that at one time in the single province of Lo-yang there were more

than 3,000 Indian monks and 10,000 Indian families to impress their national

religion and art on Chinese soil.

(source: The

Ideals of the East With Special Reference to the Art of Japan - By Kakuzo

Okakura p. 113).

Hu

Shih,

(1891-1962), Chinese philosopher in Republican China. He was ambassador to the

U.S. (1938-42) and chancellor of Peking University (1946-48). He said: Hu

Shih,

(1891-1962), Chinese philosopher in Republican China. He was ambassador to the

U.S. (1938-42) and chancellor of Peking University (1946-48). He said:

"India conquered and dominated China culturally for two thousand

years without ever

having to send a single soldier across her border."

Court Bjornstjerna

(1779-1847) author of The

Theogony of the Hindoos with their systems of Philosophy and Cosmogony says: " what may be said with certainty is that the religion of China came

from India."

Chinese authors, too, according to Mountstuart

Elphinstone (1779-1859) noted, Indian ambassadors to the court of

China.

The Mahabharata refers to China several

times, including a reference to presents brought by the Chinese at the Rajasuya

Yajna of the Pandavas; also, the Arthasastra and the Manusmriti mention China.

According to Rene Grousset (1885-1952)

French art historian

in his book Rise

and Splendour of Chinese Empire ASIN 0520005252 p.

79:

"the name China comes from "an ancient"

Sanskrit name for the regions to the east, and not, as often supposed, from the

name of the state of Ch'in," the first dynasty established by Shih Huang Ti

in 221 B.C.

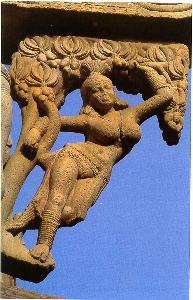

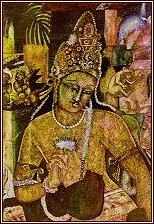

Brahma - Chinese version.

(image source: Our Heritage and Its Significance - By S. R.

Sharma).

***

The Sanskrit name Cina for China could have been derived from the

small state of that name in Chan-si in the northwest of China, which flourished

in the fourth century B.C. Scholars have pointed out that the Chinese word

for lion, shih, used long before the Chin dynasty, was derived from the Sanskrit

word, simha, and that the Greek word for China, Tzinista, used by some later

writers, appears to be derivative of the Sanskrit Chinasthana. The Chinese literature of the third century is full of

geographic and mythological elements derived from India.

" I see no reason to doubt," comments Arthur

Waley in his book, The

Way and its Power, "that the

'holy mountain-men' (sheng-hsien) described by Lieh Tzu are Indian rishi;

and when we read in Chuang Tzu of certain Taoists who practiced movements

very similar to the asanas of Hindu yoga, it is at least a possibility

that some knowledge of the yoga technique which these rishi used had also

drifted into China."

Both Sir L. Wooley and

British historian Arnold Toynbee speak

of an earlier ready-made culture coming to China. They were right. That was the

Vedic Hindu culture from India with its Sanskrit language and sacred

scripts. The contemporary astronomical expertise of the Chinese, as

evidenced by their records of eclipses; the philosophy of the Chinese their

statecraft, all point to a Vedic origin. That is why from the earliest times we

find Chinese travelers visiting India very often to renew their educational and

spiritual links.

Author Kenneth

Ch'en has said:

"Neo-Confucianism was stimulated in its

development by a number of Buddhist ideas. Certain features of Taoism, such as

its canon and pantheon, was taken over from Buddhism. Works and phrases in the

Chinese language owe their origin to terms introduced by Buddhism. Chinese

language owe their origin to terms introduced by Buddhism, while in

astronomical, calendrical, and medical studies the Chinese benefited from

information introduced by Indian Buddhist monks. Finally, and most important of

all, the religious life of the Chinese was affected profoundly by the doctrines

and practices, pantheon and ceremonies brought in by the Indian

religion." "Neo-Confucianism was stimulated in its

development by a number of Buddhist ideas. Certain features of Taoism, such as

its canon and pantheon, was taken over from Buddhism. Works and phrases in the

Chinese language owe their origin to terms introduced by Buddhism. Chinese

language owe their origin to terms introduced by Buddhism, while in

astronomical, calendrical, and medical studies the Chinese benefited from

information introduced by Indian Buddhist monks. Finally, and most important of

all, the religious life of the Chinese was affected profoundly by the doctrines

and practices, pantheon and ceremonies brought in by the Indian

religion."

(source: Buddhism

in China - By Kenneth Ch'en ISBN 0691000158 p. 3).

How China was part of the Indian Vedic empire

is explained by Professor G. Phillips on

page 585 in the 1965 edition of the Journal of

the Royal Asiatic Society. He remarks,

"The maritime intercourse of India and China dates from a much earlier

period, from about 680 B.C. when the sea traders of the Indian Ocean whose

chiefs were Hindus founded a colony called Lang-ga, after the Indian named Lanka

of Ceylon, about the present gulf of Kias-Tehoa, where they arrived in vessels

having prows shaped like the heads of birds or animals after the pattern

specified in the Yukti Kalpataru

(an ancient Sanskrit technological text) and exemplified in the ships and boats

of old Indian arts."

Chinese

historian Dr. Li-Chi also discovered an astonishing resemblance between the

Chinese clay pottery and the pottery discovered at Mohenja daro on the Indian

continent. Yuag Xianji,

member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, speaking at

the C. P. Ramaswamy Aiyar Foundation, Madras, March 27 1984 said,

" Recent

discoveries of ruins of Hindu temples in Southeast China provided further

evidence of Hinduism in China. Both Buddhism and Hinduism were patronized by the

rulers. In the 6th century A.D. the royal family was Hindu for two generations.

The following Tang dynasty (7th to the 9th century A.D.) also patronized both

Hinduism and Buddhism because the latter was but a branch of Hinduism. Religious

wars were unknown in ancient China. There was extensive maritime trade and

religious exchanges between India and China at this period (Ad 1-600) and

the massive expansion of Indian influence into southern China through Jih-nan

and Chiao-chih, in what is now northern Vietnam.

Albert Etienne Terrien de

Lacouperie, author of Western

Origins of Chinese Civilization states that the maritime intercourse

of India with China dates from about 680 B.C. when the sea traders of the Indian

ocean" whose "Chiefs were Hindus" founded a colony, called Lang-ga,

after the Indian name Lanka, about the present gulf of Kiaotchoa....And

throughout this period the monopoly of the sea borne trade of China was in their

hands."

In the second century A.D., Indians from the

Sindhu during the time of Rudradaman, the Khshatrapa Satrap of Kattiawad, took

presents by sea to China.

(source: Milinda Panha -

Vide p. 127-327). Refer to

Marco Polo’s epic journey to China was a big con –

Team Folks

The sea route from India and China through the

port of Tamraliptis was under the special protection of the Indian kings. When

the Chinese pilgrim, Hiuen-Tsiang, wanted to

return to China in A.D. 645, Bhashkarvarman the king of Kamrup (Assam) and a

vassal of King Harsha, told him: "But I know not, if you prefer to go, by

what route you propose to return; if you select the southern sea route, then I

will send official attendants to accompany you." Itsing

sailed from China for India in A.D. 671 and returned to China twenty-four years

later by the sea route from Tamralipiti. The sea route from India and China through the

port of Tamraliptis was under the special protection of the Indian kings. When

the Chinese pilgrim, Hiuen-Tsiang, wanted to

return to China in A.D. 645, Bhashkarvarman the king of Kamrup (Assam) and a

vassal of King Harsha, told him: "But I know not, if you prefer to go, by

what route you propose to return; if you select the southern sea route, then I

will send official attendants to accompany you." Itsing

sailed from China for India in A.D. 671 and returned to China twenty-four years

later by the sea route from Tamralipiti.

Through

its compassionate Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, and its promise of salvation to all

alike, its emphasis on piety, meditation, its attractive rituals and festivals,

its universality and its tolerance, "the religious life of the Chinese has

been enriched, deepened, broadened, and made more meaningful in terms of human

sympathy, love, and compassion for all living creatures." The

doctrine

of karma brought spiritual consolation to

innumerable people. The concept of karma is to be found in all types of Chinese

literature from poetry to popular tales.

India never imposed her ideas or culture on any nation by military force, not

even on the small countries in her neighborhood, and in the case of China, it

would have been virtually impossible to do so since China has been the more

powerful of the two. So the expansion of Indian culture into China is a monument

to human understanding and cultural co-operation - the outcome of a voluntary

quest for learning. While China almost completely suppressed other foreign

religions, such as Zoranstrianism, Nestorian Christianity, and to some extent

Manichaeanism, she could not uproot Buddhism. At times, Buddhism was persecuted,

but for two thousand years it continued to Indianize Chinese life even after it

had ceased to be a vital force in the homeland and long after it had lost its

place as the dominant religion of China. In fact, Indianization became

more powerful and effective after it was thought that Buddhism had been killed

in China.

The introduction of Buddhism is one of the most

important events in Chinese history, and since its inception it has been a major

factor in Chinese civilization. The Chinese have

freely acknowledged their debt to India, often referring to her as the

"Teacher of China," and Chinese Buddhists have pictured India as a

Western Paradise, Sukhavati. That Chinese

philosophy blossomed afresh after the impact of Buddhism indicates both a

response to and a borrowing of Indian ideas. The advent of Buddhism meant for

many Chinese a new way of life, and for all Chinese, a means of reassessing

their traditional beliefs. A new conception of the universe developed, and the

entire Chinese way of life was slowly but surely altered. The change was so

gradual and so universal that few people realized it was happening.

The Chinese Quietists practiced a form of

self-hypnosis which has an indisputably close resemblance to Indian

Yoga.

The Chinese Taoist philosopher Liu-An (Huai-nan-tzu)

who died in 122 B. C, makes

use "of a cosmology in his book which is clearly of Buddhist

inspiration." The Chinese Quietists practiced a form of

self-hypnosis which has an indisputably close resemblance to Indian

Yoga.

The Chinese Taoist philosopher Liu-An (Huai-nan-tzu)

who died in 122 B. C, makes

use "of a cosmology in his book which is clearly of Buddhist

inspiration."

The

first mention of India to be found in Chinese records is in connection with the

mission to Ta-hsia (Bacteriana) of a talented and courageous Chinese envoy, Chang

Chien (Kien), about 138 B.C. Fourteen years

later, having escaped after ten years as a captive of the Huns, he returned home

and in his report to the Chinese Emperor he referred to the country of Shen-tu

(India) to the southeast of the Yueh-chih (Jou-Chih) country. There are other

traditional stories suggestive of earlier links, but Chang Chien's reference to

Indian trade with the southwestern districts of China along the overland route

corresponding to the modern Yunnan road indicates the existence of some sort of

commercial relations well before the second century B.C. The find of

Chinese coins at Mysore, dated 138 B.C. suggests maritime relations between

India and China existed in the second century B.C. Passages in a Chinese text

vaguely refer to Chinese trade relations with countries in the China Sea and

Indian Ocean, such as Huang-che (Kanchi or a place in the Ganges delta), as well

as to the exchange of diplomatic missions.

Top of Page

Trade & Commerce

The chronicle 'Sung-chu'

states that all the precious things of land and water came from India. Gems

made of rhinoceros' horns and king-fishers' stones, serpent pearls and asbestos

cloth, they are being innumerable varieties of these curiosities, were imported

into China from India. According to the Chin-hsi-yu-chiu-t'

u rare stone came to China from the countries of Chi-pin (Gandhara or Kashmir).

Moreover, po-tie ( a fine textile, probably muslin) was produced in India; and

as early as A.D. 430 Indian po-tie was sent to China from Ho-lo-tan or Java. In

A.D. 519, King Jayavarman of Fu-nan (Kamboja/Cambodia) offered saffron with

storax and other aromatics to the Chinese court. Laufer also suggests that in

the sixth century saffron was traded from India to Cambodia. In the T'ang

Annals, India in her trade with Cambodia and the interior orient,

"export to those countries diamonds, sandalwood and saffron." India

was a good market for Chinese silk. Kalidasa

mentions this silk fabric (Chinamsuka) as one of the most fashionable textiles

among the richer sections of society. Silk and silk-products were also much

demanded luxury articles even in the reign of Harshavardhana. The countries

lying on the route from Kashgar (India) to China, were collectively called by

historians and geographers as 'Ser-India', first imbibed Indian culture and then

developed into important trade centers.

(source:

Cultural

Heritage of Ancient India - By Sachindra Kumar Maity p.119-124).

For more information refer to chapter on Suvarnabhumi

and Seafaring in Ancient India).

There can be little dispute that trade was the main

motivation for these early contacts. This is supported by finds of beads and

pottery, in addition to specific references in historical texts. By the early

centuries of the Christian era, Sino-Indian trade appears to have assumed

considerable proportions. Chinese silk, Chinamsuka, and later porcelain

were highly prized in India, and Indian textiles were sold in southwest China.

The similarity between the Chinese and Indian words for vermilion and bamboo,

ch'in-tung and ki-chok, and sindura and kichaka, also indicates commercial

links. At least by the fifth century, India was exporting to China wootz steel

(wootz

from the Indian Kanarese word ukku), which was produced by fusing magnetic iron

by carbonaceous matter.

With goods came ideas. It has often been contended that

merchants were not likely to have been interested in philosophy or capable of

the exchange of ideas. This is an erroneous belief which disregards historical

evidence and, as Arthur Waley points out, is

"derived

from a false analogy between East and West. It is quite true that Marco polo 'songeait

surtout a son negoce'. But

the same can hardly be said of Indian or Chinese merchants.

Buddhist legend, for example, teems with merchants reputedly capable of

discussing metaphysical questions; and in China Lu Puwei, compiler of

philosophical encyclopedia Lu Shih Ch'un Chiu, was himself a merchant. Legend

even makes a merchant of Kuan Chung; which at any rate shows that philosophy and

trade were not currently supposed to be incompatible." With goods came ideas. It has often been contended that

merchants were not likely to have been interested in philosophy or capable of

the exchange of ideas. This is an erroneous belief which disregards historical

evidence and, as Arthur Waley points out, is

"derived

from a false analogy between East and West. It is quite true that Marco polo 'songeait

surtout a son negoce'. But

the same can hardly be said of Indian or Chinese merchants.

Buddhist legend, for example, teems with merchants reputedly capable of

discussing metaphysical questions; and in China Lu Puwei, compiler of

philosophical encyclopedia Lu Shih Ch'un Chiu, was himself a merchant. Legend

even makes a merchant of Kuan Chung; which at any rate shows that philosophy and

trade were not currently supposed to be incompatible."

India had contact with China from the early

period through three routes. One was through the Central Asian region, the

second was through Yunan and Burma. The third was by sea to the South Indian

ports. The Arthasastra, the Mahabharata, and the Manu-Smriti show knowledge of

China. Through all these routes trade and Hindu culture passed to China. Indian

arts and sciences were carried to China along with Buddhism. Images, rock-cut

caves and the fresco paintings show distinctly Indian influence on the Chinese

art. Indian astronomy, mathematics and medicine were spread in China by the

scholars who visited it. Several Sanskrit works on these sciences were

translated into Chinese.

Chushu-King, a Chinese monk started for India in

260 A.D. But he returned from Khotan. Fa-hien, the first Chinese pilgrim to

India stayed here during the Gupta period for some years. Che-mong another monk

accompanied by a few others spent 20 years (404-424) in the pilgrimage of India.

Hieun Tsang and I-Tsing during the 7th century are well-known. On his return to

China, Hiuen Tsang was given a great national welcome by his emperor and the

people as well.

(source: Ancient Indian

History and Culture - By Chidambara Kulkarni p.233 -234).

Land and Sea Routes

The art of shipbuilding and navigation in India and China at the time was

sufficiently advanced for oceanic crossings. Indian ships operating between Indian and

South-east Asian ports were large and well equipped to sail cross the Bay of Bengal. When

the Chinese Buddhist scholar, Fa-hsien,

returned from India, his ship carried a crew of more than two hundred

persons and did not sail along the coasts but directly across the ocean. Such ships

were larger than those Columbus used to negotiate the Atlantic a thousand years later. Uttaraptha

was the Sanskrit name of the ancient highway which connected India with China,

Russia and Persia (Iran).

The art of shipbuilding and navigation in India and China at the time was

sufficiently advanced for oceanic crossings. Indian ships operating between Indian and

South-east Asian ports were large and well equipped to sail cross the Bay of Bengal. When

the Chinese Buddhist scholar, Fa-hsien,

returned from India, his ship carried a crew of more than two hundred

persons and did not sail along the coasts but directly across the ocean. Such ships

were larger than those Columbus used to negotiate the Atlantic a thousand years later. Uttaraptha

was the Sanskrit name of the ancient highway which connected India with China,

Russia and Persia (Iran).

The trade routes between China and India, by both land

and sea, were long and perilous, often requiring considerably more than two

years to negotiate. The overland routes were much older and more often used, but

the sea routes gained popularity with progress in shipbuilding and seamanship.

Formidable and frightening as the physiography of the land routes was, the

traffic through the passes and along the circuitous routes around the mountains

was fairly vigorous.

According to the work of mediaeval times,

Yukti Kalpataru, which gives a fund of information

about shipbuilding, India built large vessels from 200 B.C. to the close of the sixteenth

century. A Chinese chronicler mentions ships of Southern Asia that could carry as many as

one thousand persons, and were manned mainly by Malayan crews.

Long before

the northwestern routes were opened about the second century B.C. and long

before the development of these Indianized states, there were two other routes

from India to China. One of these began at Pataliputra (modern Patna), passed

through Assam (Kamarupa of old) and Upper Burma near Bhamo, and proceeded over

the mountains and across the river valleys to Yunnanfu (Kunming), the main city

of the southern province of China. The other route lay through Nepal and Tibet,

was developed much later in the middle of the seventh century when Tibet had

accepted Buddhism.

In addition to land routes, there was an important sea

link between India and China through Southeast Asia. During the course of the

first few centuries of the Christian era, a number of Indianized states had been

founded all over Southeast Asia. Both cultures met in this region, and the

Indianized states served as an intermediary stave for the further transmission

of Indian culture and Buddhism to China. In addition to land routes, there was an important sea

link between India and China through Southeast Asia. During the course of the

first few centuries of the Christian era, a number of Indianized states had been

founded all over Southeast Asia. Both cultures met in this region, and the

Indianized states served as an intermediary stave for the further transmission

of Indian culture and Buddhism to China.

Ancient Greek geographers knew of Southeast Asia and

China (Thinae) were accessible by sea. Ptolemy mentions an important but

unidentified Chinese port on the Tonkinese coast. Ports on the western coast of

India were Bharukaccha (Broach); Surparka (Sopara); Kalyana; on the Bay of

Bengal at the mouth of the Kaveripattam (Puhar); and at the mouth of the Ganges,

Tamaralipti (Tamluk). At least two of these ports on the Bay of Bengal -

Kaveripattam and Tamaralipti - were known to the Greek sailors as Khaberos and

Tamalitis. At first Indian ships sailed to Tonkin (Kiao-Che) which was the

principal port of China, Tonkin being a Chinese protectorate. Later all foreign

ships were required to sail to Canton in China proper. Canton became a

prosperous port and from the seventh century onward the most important landing

place for Buddhist monks arriving from India. Generally Chinese monks set out

for the famous centers of learning in India, like the University of Taxila, and

Nalanda.

India

had census enumeration earlier than China, since such enumeration is mentioned

in Kautilya’s Arthasastra. China had its first census in 2 A.D.

Top of Page

Contributions

Mathematics:

The Chinese were familiar with Indian mathematics,

and, in fact, continued to study it long after the period of intellectual

intercourse between India and China had ceased."

(source: Cited in Sarkar,

Hindu Achievements in Exact Science, p. 14).

Literature: The

great literary activity of the Buddhist scholars naturally had a permanent

influence on Chinese literature, one of the oldest in the world. In a recent

study a Chinese scholar Lai Ming,

says that a significant feature in the development of Chinese literature has

been the "the immense influence of Buddhist literature on the development

of every sphere of Chinese literature since the Eastern Chin period (317

A.D.)." The Buddhist sutras were written in combined prose and rhymed

verse, a literary form unknown in China at the time. The Chinese language when

pronounced in the Sanskrit polyphonic manner was likely to sound hurried and

abrupt, and to chant the Sanskrit verses in monophthongal Chinese prolonged the

verse so much the rhymes were lost. Hence, to make the Chinese sutras pleasant

to listen to, the Chinese language had to be modified to accommodate Sanskrit

sounds. Consequently, in 489, Yung Ming, Prince

of Ching Ling, convened a conference of

Buddhist monks at his capital to differentiate between, and define the tones of,

the Chinese language for reading Buddhist sutras and for changing the verses. A

new theory emerged called the Theory of Four Tones. The introduction into China

of highly imaginative literature such as the Mahayana sutras and the Indian

epics, like Ramayana and Mahabharata,

infused into Chinese literature the quality of imagination which had been

hitherto lacking. Taoist literature, such as the book Chuang-tzu, did perhaps

show some quality of imaginative power, but on the whole Chinese literature,

especially Confucianist, was narrow, formal, restricted, and

unimaginative. Literature: The

great literary activity of the Buddhist scholars naturally had a permanent

influence on Chinese literature, one of the oldest in the world. In a recent

study a Chinese scholar Lai Ming,

says that a significant feature in the development of Chinese literature has

been the "the immense influence of Buddhist literature on the development

of every sphere of Chinese literature since the Eastern Chin period (317

A.D.)." The Buddhist sutras were written in combined prose and rhymed

verse, a literary form unknown in China at the time. The Chinese language when

pronounced in the Sanskrit polyphonic manner was likely to sound hurried and

abrupt, and to chant the Sanskrit verses in monophthongal Chinese prolonged the

verse so much the rhymes were lost. Hence, to make the Chinese sutras pleasant

to listen to, the Chinese language had to be modified to accommodate Sanskrit

sounds. Consequently, in 489, Yung Ming, Prince

of Ching Ling, convened a conference of

Buddhist monks at his capital to differentiate between, and define the tones of,

the Chinese language for reading Buddhist sutras and for changing the verses. A

new theory emerged called the Theory of Four Tones. The introduction into China

of highly imaginative literature such as the Mahayana sutras and the Indian

epics, like Ramayana and Mahabharata,

infused into Chinese literature the quality of imagination which had been

hitherto lacking. Taoist literature, such as the book Chuang-tzu, did perhaps

show some quality of imaginative power, but on the whole Chinese literature,

especially Confucianist, was narrow, formal, restricted, and

unimaginative.

Mythology: The

Chinese sense of realism was so intense that there was hardly any mythology in

ancient China, and they have produced few fairy tales of their own. Most of

their finest fairy tales were originally brought to China by Indian monks in the

first millennium. The Buddhists used them to make their sermons more agreeable

and lucid. The tales eventually spread throughout the country, assuming a

Chinese appearance conformable to their new environment. For example, the

stories of Chinese plays such as A Play of Thunder-Peak, A Dream of

Butterfly, and A Record of Southern Trees were of Buddhist

origin.

Drama: Chinese

drama assimilated Indian features in three stages. First, the story, characters,

and technique were all borrowed from India; later, Indian technique gave way to

Chinese; and finally, the story was modified and the characters became Chinese

also. There are many dimensions to Chinese drama, and it is not easy to place

them accurately in history. However, the twelfth century provides the

first-known record of the performance of a play, a Buddhist miracle-play called

Mu-lien Rescues his Mother based on an episode in the Indian

epic, the Mahabharata. The subject matter of

the Buddhist adaptation of the story, in which Maudgalyayana (Mu-lien in

Chinese) rescues the mother from hell, occurs in a Tun-huang pien wen.

Significantly, the play was first performed at the Northern Sung capital by

professionals before a religious festival. Drama: Chinese

drama assimilated Indian features in three stages. First, the story, characters,

and technique were all borrowed from India; later, Indian technique gave way to

Chinese; and finally, the story was modified and the characters became Chinese

also. There are many dimensions to Chinese drama, and it is not easy to place

them accurately in history. However, the twelfth century provides the

first-known record of the performance of a play, a Buddhist miracle-play called

Mu-lien Rescues his Mother based on an episode in the Indian

epic, the Mahabharata. The subject matter of

the Buddhist adaptation of the story, in which Maudgalyayana (Mu-lien in

Chinese) rescues the mother from hell, occurs in a Tun-huang pien wen.

Significantly, the play was first performed at the Northern Sung capital by

professionals before a religious festival.

***

Amartya

Sen Nobel

Prize winner writes in the Times of India:

"It

is not often realized "that even such a central term in Chinese culture as

Mandarin is derived from a Sanskrit word, namely Mantri

which went from India to China via Malaya."

Chinese translation - the first printed book in

the world was the Chinese translation by Kumarajiva (a half Indian half Turkish

scholar) of a Buddhist Sanskrit text, Vajrachchedikaprajnyaparamita

(source: India,

according to Amartya Sen - by M.V.

Kamath

Publication:

Afternoon Despatch & Courier).***

Grammar:

Phrases

and words coined by Buddhist scholars enriched the Chinese vocabulary by more

than thirty-five thousand words. As the assimilation was spread over a long

period of time, the Chinese accepted these words as a matter of course without

even suspecting their foreign origin. Even today words of Buddhist origin are

widely used in China from the folklore of peasants to the formal language of the

intelligentsia. For example, poli for glass in the name of many precious

and semi-precious stones is of Sanskrit origin.

Cha-na, an instant, from kshana; t'a, pagoda, from stupa;

mo-li, jasmine, from mallika, and terms for many trees and plants

are amongst the many thousands of Chinese words of Indian origin. Indian grammar

also undoubtedly stimulated Chinese philological study. Chinese script consists

of numerous symbols, which in their earliest stage were chiefly pictographic and

ideographic. Grammar:

Phrases

and words coined by Buddhist scholars enriched the Chinese vocabulary by more

than thirty-five thousand words. As the assimilation was spread over a long

period of time, the Chinese accepted these words as a matter of course without

even suspecting their foreign origin. Even today words of Buddhist origin are

widely used in China from the folklore of peasants to the formal language of the

intelligentsia. For example, poli for glass in the name of many precious

and semi-precious stones is of Sanskrit origin.

Cha-na, an instant, from kshana; t'a, pagoda, from stupa;

mo-li, jasmine, from mallika, and terms for many trees and plants

are amongst the many thousands of Chinese words of Indian origin. Indian grammar

also undoubtedly stimulated Chinese philological study. Chinese script consists

of numerous symbols, which in their earliest stage were chiefly pictographic and

ideographic.

The word used in the old Sanskrit for

the Chinese Emperor is deva-putra,

which is an exact translation of ' Son of Heaven.'

I-tsing,

a famous pilgrim, himself a fine

scholar of Sanskrit, praises the language and says it is respected in far

countries in the north and south. ..'How much

more then should people of the divine land (China), as well as the celestial

store house (India), teach the real rules of the language.'

Jawaharlal Nehru has

commented:

"Sanskrit scholarship must have been fairly widespread in China. It is

interesting to find that some Chinese scholars tried to introduce Sanskrit

phonetics into the Chinese language. A well-known example of this is that of the

monk Shon Wen, who lived at the time of the Tang dynasty. He tried to develop an

alphabetical system along these lines in Chinese."

(source: The Discovery

of India - By Jawaharlal Nehru p.

197-198).

Art: Indian art

also reached China, mainly through Central Asia, although some works of Buddhist

art came by sea. Monks and their retinues, and traders brought Buddha

statues, models of Hindu temples, and other objects of art to China. Fa-hsien

made drawings of images whilst at Tamralipiti. Hsuan-tsang

returned with several golden and sandalwood figures of the Buddha; and Hui-lun

with a model of the Nalanda Mahavihara. Wang

Huan-ts'e, who went to India several times,

collected many drawings of Buddhist images, including a copy of the Buddha image

at Bodhgaya; this was deposited at the Imperial palace and served as a model of

the image in Ko-ngai-see temple. The most famous icon of East Asian Buddhism

know as the "Udayana" image was reported to have been brought by the

first Indian missionaries in 67, although there are various legends associated

with this image and many scholars believe it was brought by Kumarajiva.

However, this influx of Indian art was incidental and intermittent, and was

destined to be absorbed by Chinese art. This combination resulted in a Buddhist

art of exceptional beauty. Art: Indian art

also reached China, mainly through Central Asia, although some works of Buddhist

art came by sea. Monks and their retinues, and traders brought Buddha

statues, models of Hindu temples, and other objects of art to China. Fa-hsien

made drawings of images whilst at Tamralipiti. Hsuan-tsang

returned with several golden and sandalwood figures of the Buddha; and Hui-lun

with a model of the Nalanda Mahavihara. Wang

Huan-ts'e, who went to India several times,

collected many drawings of Buddhist images, including a copy of the Buddha image

at Bodhgaya; this was deposited at the Imperial palace and served as a model of

the image in Ko-ngai-see temple. The most famous icon of East Asian Buddhism

know as the "Udayana" image was reported to have been brought by the

first Indian missionaries in 67, although there are various legends associated

with this image and many scholars believe it was brought by Kumarajiva.

However, this influx of Indian art was incidental and intermittent, and was

destined to be absorbed by Chinese art. This combination resulted in a Buddhist

art of exceptional beauty.

One of the most famous caves - Ch'ien-fo-tung,

"Caves of the Thousand Buddhas,"

because there are supposed to be more than a thousand cave. So far, about five

hundred caves have been discovered. These caves were painted throughout with

murals, and were frequently furnished with numerous Buddha statues and

sculptured scenes from the Jatakas.

Many other caves were initiated in the reign of Toba

Wei Emperor, T'ai Wu. Some also contain images of Hindu deities, such as Shiva

on Nandi and Vishnu on Garuda.

Images coming from India were considered holy, as

suggested by Omura, in his History of Chinese

Sculpture. This

significantly underlines the depth of Chinese acceptance of Indian

thought.

Music:

The Chinese

did not regard music as an art to be cultivated outside the temples and

theatres. Buddhist monks who reached China brought the practice of chanting

sacred texts during religious rites. Hence, Indian melody was introduced into

Chinese music which had hitherto been rather static and restrained. Indian music was so popular in China, that

Emperor Kao-tsu (581-595) tried unsuccessfully to proscribe

it by an Imperial decree. His successor Yang-ti was also very fond of Indian

music. In Chinese annals, references are found

to visiting Indian musicians, who reached China from India, Kucha, Kashgar,

Bokhara and Cambodia. Even Joseph Needham,

the well-known advocate of Chinese cultural and scientific priority admits,

"Indian music came through Kucha to China just before the Sui period and

had a great vogue there in the hands of exponents such as Ts'ao Miao-ta of

Brahminical origin." By the end of the

sixth century, Indian music had been given state recognition. During the T'ang

period, Indian music was quite popular, especially the famous Rainbow Garment

Dance melody. Music:

The Chinese

did not regard music as an art to be cultivated outside the temples and

theatres. Buddhist monks who reached China brought the practice of chanting

sacred texts during religious rites. Hence, Indian melody was introduced into

Chinese music which had hitherto been rather static and restrained. Indian music was so popular in China, that

Emperor Kao-tsu (581-595) tried unsuccessfully to proscribe

it by an Imperial decree. His successor Yang-ti was also very fond of Indian

music. In Chinese annals, references are found

to visiting Indian musicians, who reached China from India, Kucha, Kashgar,

Bokhara and Cambodia. Even Joseph Needham,

the well-known advocate of Chinese cultural and scientific priority admits,

"Indian music came through Kucha to China just before the Sui period and

had a great vogue there in the hands of exponents such as Ts'ao Miao-ta of

Brahminical origin." By the end of the

sixth century, Indian music had been given state recognition. During the T'ang

period, Indian music was quite popular, especially the famous Rainbow Garment

Dance melody.

A contemporary Chinese poet, Po

Chu-yi, wrote a poem in praise of Indian music.

"It is little wonder," an official publication of the Chinese Republic

says, "that when a Chinese audience today hears Indian music, they feel

that while possessing a piquant Indian flavor it has a remarkable affinity with

Chinese music."

Science:

A major

Buddhist influence on Chinese science was in scientific thought itself. Buddhist

concepts, such as the infinity of space and time, and the plurality of worlds

and of time-cycles or Hindu Kalpas

(chieh) had a stimulating effect on Chinese inquiry, broadening the

Chinese outlook and better equipping it to investigate scientific problems. For

example, the Hindu doctrine of pralayas,

or recurrent world catastrophes in which sea and land were turned upside down

before another world was recreated to go through the four cycles-

differentiation (ch'eng), stagnation (chu), destruction (juai), and emptiness

(kung) - which was later adopted by Neoconfucianists, was responsible for the

Chinese recognition of the true nature of fossils long before they were

understood in Europe. Again, the Indian doctrine of Karma (tso-yeh), or

metempsychosis, influenced Chinese scientific thought on the process of

biological change involving both phylogeny and ontogeny. Buddhist iconography

contained a biological element. Buddhism introduced a highly developed theory of

logic, both formal and dialectical, and of epistemology. Science:

A major

Buddhist influence on Chinese science was in scientific thought itself. Buddhist

concepts, such as the infinity of space and time, and the plurality of worlds

and of time-cycles or Hindu Kalpas

(chieh) had a stimulating effect on Chinese inquiry, broadening the

Chinese outlook and better equipping it to investigate scientific problems. For

example, the Hindu doctrine of pralayas,

or recurrent world catastrophes in which sea and land were turned upside down

before another world was recreated to go through the four cycles-

differentiation (ch'eng), stagnation (chu), destruction (juai), and emptiness

(kung) - which was later adopted by Neoconfucianists, was responsible for the

Chinese recognition of the true nature of fossils long before they were

understood in Europe. Again, the Indian doctrine of Karma (tso-yeh), or

metempsychosis, influenced Chinese scientific thought on the process of

biological change involving both phylogeny and ontogeny. Buddhist iconography

contained a biological element. Buddhism introduced a highly developed theory of

logic, both formal and dialectical, and of epistemology.

Tantric Buddhism reached China in the eighth century

and the greatest Chinese astronomer and mathematician of his time, I-hsing

(682-727), was a Tantric Buddhist monk. While

the work of Indian mathematicians was carried westward by the Arabs and

transmitted to Europe, it was taken eastward by Indian Buddhist monks and

professional mathematicians.

Astronomy:

There is also some evidence that works on Indian astronomy were in circulation

in China well before the T'ang period. In the annuals of the Sui dynasty,

numerous Chinese translations of Indian mathematical and astronomical works are

mentioned, such as Po-lo-men Suan fa (The Hindu Arithmetical rules) and

Po-lo-men Suan King. These works have vanished, and it is impossible to assess

the degree of their influence on Chinese sciences. However, there is definite

evidence of Indian influence on Chinese astronomy and calendar studies during

the T'ang dynasty. During this period, Indian astronomers were working at the

Imperial Bureau of Astronomy which was charged with preparing accurate

calendars. Yang Ching-fang, a pupil of Amoghavajra (Pu-k'ung), wrote in 764 that

those who wished to know the positions of the five planets and predict what Hsiu

(heavenly mansion) a planet would be traversing, should adopt the Indian

calendrical methods. Five years earlier, Amoghavajra had translated an Indian

astrological work, the Hsiu Yao Ching (Hsiu and Planet Sutra), into

Chinese. Astronomy:

There is also some evidence that works on Indian astronomy were in circulation

in China well before the T'ang period. In the annuals of the Sui dynasty,

numerous Chinese translations of Indian mathematical and astronomical works are

mentioned, such as Po-lo-men Suan fa (The Hindu Arithmetical rules) and

Po-lo-men Suan King. These works have vanished, and it is impossible to assess

the degree of their influence on Chinese sciences. However, there is definite

evidence of Indian influence on Chinese astronomy and calendar studies during

the T'ang dynasty. During this period, Indian astronomers were working at the

Imperial Bureau of Astronomy which was charged with preparing accurate

calendars. Yang Ching-fang, a pupil of Amoghavajra (Pu-k'ung), wrote in 764 that

those who wished to know the positions of the five planets and predict what Hsiu

(heavenly mansion) a planet would be traversing, should adopt the Indian

calendrical methods. Five years earlier, Amoghavajra had translated an Indian

astrological work, the Hsiu Yao Ching (Hsiu and Planet Sutra), into

Chinese.

At the time there were three astronomical schools at

Chang-an: Gautama (Chhuthan), Kasyapa (Chiayeh), and Kumara (Chumolo). In 684

one of the members of the Gautama school, Lo presented a calendar, Kuang-tse-li,

which has been in use for three years, to the Empress Wu. Later, in 718, another

member of the school, Hsi-ta (Siddhartha), presented to the Emperor a calendar,

Chiu-che-li, which was almost a direct translation of an Indian calendar, Navagraha

Siddhanta of Varahamihira, and which is still

preserved in the T'ang period collection. It was in use for four years. In 729

Siddhartha compiled a treatise based on this calendar which is the greatest

known collection of ancient Chinese astronomical writings. This was the first

time that a zero symbol appeared in a Chinese text, but, even more important,

this work also contained a table of sines, which were typically Indian. I-hsing

(682-727) was associated with the Kumara school and was much influenced by

Indian astronomy. Indian influence can also be seen in the nine planets he

introduced into his calendar, Ta-yen-li. The nine planets included the sun,

moon, five known planets, and two new planets, Rahu

and Ketu, by which the Indian astronomers

represented the ascending and descending nodes of the moon. At the time there were three astronomical schools at

Chang-an: Gautama (Chhuthan), Kasyapa (Chiayeh), and Kumara (Chumolo). In 684

one of the members of the Gautama school, Lo presented a calendar, Kuang-tse-li,

which has been in use for three years, to the Empress Wu. Later, in 718, another

member of the school, Hsi-ta (Siddhartha), presented to the Emperor a calendar,

Chiu-che-li, which was almost a direct translation of an Indian calendar, Navagraha

Siddhanta of Varahamihira, and which is still

preserved in the T'ang period collection. It was in use for four years. In 729

Siddhartha compiled a treatise based on this calendar which is the greatest

known collection of ancient Chinese astronomical writings. This was the first

time that a zero symbol appeared in a Chinese text, but, even more important,

this work also contained a table of sines, which were typically Indian. I-hsing

(682-727) was associated with the Kumara school and was much influenced by

Indian astronomy. Indian influence can also be seen in the nine planets he

introduced into his calendar, Ta-yen-li. The nine planets included the sun,

moon, five known planets, and two new planets, Rahu

and Ketu, by which the Indian astronomers

represented the ascending and descending nodes of the moon.

Chinese

New Year

Dates from 2600 BC - A complete cycle takes 60 years, divided into 12 year

elements. Each of these 12 years is named after an animal

favored by the Buddha.

(source:

China

welcomes the New Year - BBC). Chinese 60 year cycle has

strong resemblance to Tamil Calendar and Indian Hindu Calendars.

For more refer to The

Tamil Calendar).

Medicine

Chinese

medicine, was influenced by Ayurveda, and similarities include the extensive use

of natural herbs.

(source:

Balm from the East - By Jenny Hontz - LA

Times).

According to Terence

Duke " Many Buddhists were familiar with the extensive knowledge

of surgery common to Indian medicine and this aided them both in spreading the

teachings and in their practice of diagnosis and therapy. Surgical technique was

almost unknown within China prior to the arrival of Buddhism.." The

renowned Buddhist teacher Najarjuna is said

to have translated at least two traditional works dealing with healing and

medicines in the first centuries of our era. A section of his

Maha-Prajnaparamita Sutra is quoted by the Chinese monk I Tsing in his

commentary upon the five winds (Chinese: Wu Fung; Japanese: Gofu). This

description enables us to see that the breath Hatha

Yoga termed prana is in fact forming only part of a wider system

known in Buddhism."

(source:

The

Boddhisattva Warriors: The Origin, Inner Philosophy, History and Symbolism of

the Buddhist Martial Art Within India and China p.139-145).

Evidence

of Indian influence on Chinese medicine is even more definite. A number of

Indian medical treatises are found in Chinese Buddhist collections: for example,

the Ravanakumaratantra and Kasyapasamhita. From its very inception, Buddhism

stressed the importance of health and the prevention and cure of mental and

physical ailments. Indian medical texts were

widely known in Central Asia, where parts of the original texts on Ayur Veda

have been found as well as numerous translations. Evidence

of Indian influence on Chinese medicine is even more definite. A number of

Indian medical treatises are found in Chinese Buddhist collections: for example,

the Ravanakumaratantra and Kasyapasamhita. From its very inception, Buddhism

stressed the importance of health and the prevention and cure of mental and

physical ailments. Indian medical texts were

widely known in Central Asia, where parts of the original texts on Ayur Veda

have been found as well as numerous translations.

The T'ang emperors patronized Indian thaumaturges

(Tantric

Yogis) who were believed to possess secret methods of rejuvenation. Wang

Hsuan-chao, who returned to India after the death of King Harsha had been

charged by the Chinese Emperor in 664 to bring back Indian medicines and

physicians.

Considering that Indian medicine, especially

operative surgery, was highly developed for the time, it is not surprising that

the Chinese, like the Arabs, were captivated by Indian medical skills and drugs.

Castration was performed by Chinese methods but other surgical techniques, such

as laparotomy, trepanation, and removal of cataracts, as well as inoculation for

smallpox, were influenced by Indian practices.

Acupuncture

In modern day acupuncture

lore, there is recounted a legend that the discovery of the vital bodily points

began within India as a result of combative research studies undertaken by the

Indian ksatreya warriors in order to discover the vital (and deadly) points of

the body which could be struck during hand-to-hand encounters.

It is said that they experimented upon prisoners by piercing their bodies

with the iron and stone "needles' daggers called Suci daggers. common

to their infantry and foot soldiers, in order to determine these points.

This Chinese legend reflects and

complements the traditional Indian account of its origins, where it is said that

in the aftermath of battles it was noticed that sometimes therapeutic effects

arose from superficial arrow or dagger wounds incurred by the Khastriya in

battle.

(source: The

Boddhisattva Warriors: The Origin, Inner Philosophy, History and Symbolism of

the Buddhist Martial Art Within India and China p.139-145).

The alternative form of medicine known as acupuncture

is believed to have originated in China. In Korean academics, students are

correctly told that acupuncture originated in India. An ancient Sanskrit text on

acupuncture preserved in the Ceylonese National Museum at Columbo in Sri

Lanka.

The

custom of ancestor worship was an adoption of Indian custom. There is

presence of Indian motifs in various Buddhist caves in China.

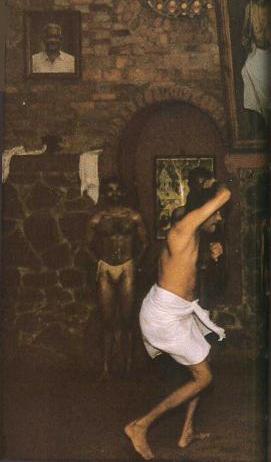

Martial Arts/Games

Fighting

without weapons was a specialty of the Ksatreya (caste of Ancient India) and foot

soldier alike.

Danger and Divinity:

Originating at least 1,300 years ago, India's Kalaripayit is the oldest martial

art taught today. It is also one of the most potentially violent. Weaponless but

nimble, a karaipayit master displays for his students how to meet the attack of

an armed opponent.

Watch

Kalari

Martial Arts and

Silambam

Martial Arts video and

How Kung Fu originated from Martial Arts practices of Hinduism

***

According to author

Terence Dukes:

"Fighting

without weapons was a specialty of the Ksatreya (caste of Ancient India)and foot

soldier alike. For the Ksatreya it was simply part and parcel of their all

around training, but for the lowly peasant it was essential. We read in the

Vedas of men unable to afford armor who bound their heads with turbans called Usnisa

to protect themselves from sword and axe blows. "Fighting

without weapons was a specialty of the Ksatreya (caste of Ancient India)and foot

soldier alike. For the Ksatreya it was simply part and parcel of their all

around training, but for the lowly peasant it was essential. We read in the

Vedas of men unable to afford armor who bound their heads with turbans called Usnisa

to protect themselves from sword and axe blows.

Watch Kalari

Martial Arts and

Silambam

Martial Arts video

Fighting on foot for a Ksatreya was necessary in case he was unseated from his

chariot or horse and found himself without weapons.

Although the high ethical

code of the Ksatreya forbid anyone but another Ksatreya from attacking him,

doubtless such morals were not always observed, and when faced with an

unscrupulous opponent, the Ksatreya needed to be able to defend himself, and

developed, therefore, a very effective form of hand-to-hand combat that combined

techniques of wrestling, throws, and hand strikes.

Tactics and evasion were

formulated that were later passed on to successive generations. This skill was

called Vajramukhti, a name meaning "thunderbolt closed - or clasped -

hands."

The tile Vajramukti referred to the usage of the hands in a manner

as powerful as the Vajra maces of traditional warfare. Vajramukti was practiced

in peacetime by means of regular physical training sessions and these utilized

sequences of attack and defense technically termed in Sanskrit nata." The tile Vajramukti referred to the usage of the hands in a manner

as powerful as the Vajra maces of traditional warfare. Vajramukti was practiced

in peacetime by means of regular physical training sessions and these utilized

sequences of attack and defense technically termed in Sanskrit nata."

"Prior to and during the life of the Buddha various principles were

embodied within the warrior caste known as the Ksatreya

(Japanese: Setsuri). This title - stemming from Sanskrit root Ksetr meaning

"power," described an elite force of usually royal or noble-born

warriors who were trained from infancy in a wide variety of military and martial

arts, both armed and unarmed.

In China, the Ksatreya were considered to have

descended from the deity Ping Wang (Japanese: Byo O), the "Lord of those

who keep things calm." Ksatreyas were like the Peace force - to keep kings and

people in order. Military commanders were called Senani - a name reminiscent of

the Japanese term Sensei which describes a similar status. The Japanese samurai

also had similar traits to the Ksatreya. Their battle practices and techniques

are often so close to that of the Ksatreya that we must assume the former came

from India perhaps via China. The traditions of sacred Swords, of honorable

self-sacrifice, and service to one's Lord are all found first in

India.

"In

ancient Hinduism, nata was acknowledged as a

spiritual study and conferred as a ruling deity, Nataraja,

representing the awakening of wisdom through physical and mental concentration. However,

after the Muslim invasion of India and its brutal destruction of Buddhist and

Hindu culture and religion, the Ksatreya art of nata was dispersed and many of

its teachers slain. This indigenous martial arts, under the name of Kalari

or Kalaripayit exists only in South India today. Originating at least 1,300 years ago, India's

Kalaripayit is the oldest martial art taught today. It is also the most

potentially violent, because students advance from unarmed combat to the use of

swords, sharpened flexible metal lashes, and peculiar three-bladed daggers.

When Buddhism came to influence India (circa 500

B.c), the Deity Nataraja was converted to

become one of the four protectors of Buddhism, and was renamed Nar (y)ayana Deva

(Chinese: Na Lo Yen Tien). He is said to be a protector of the Eastern

Hemisphere of the mandala."

INDIA

Ksatreya Vajramukti

Simhanta

Bodhisattva Vajramukti

Trisatyabhumi

Trican Nata

Dharmapala

Mahabhuta Pratima

CHINA

Seng Cha

Pu Sa Chin Kang Chuan

(Bodhisattva Vajramukti

(Po Fu) (Huo Ming) (Pa She) (Pai Chin)

Seng Ping

Chuan Fa or Kung Fu

(Karate) (Tae Kwon

Do) (Thai Boxing) (Ju Jitsu) (Judo) (Aikido)

(source: The

Boddhisattva Warriors: The Origin, Inner Philosophy, History and Symbolism of

the Buddhist Martial Art Within India and China p.3

- 158-174 and 242).

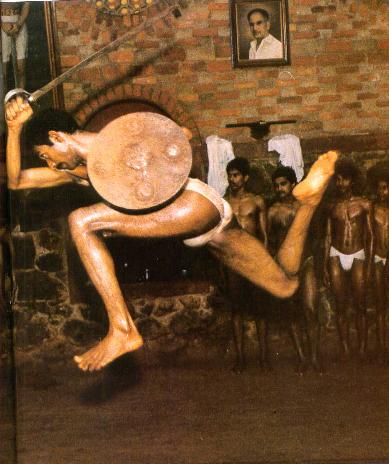

Kalaripayattu,

literally “the way of the battlefield,” still survives in Kerala,

where it is often dedicated to Mahakali. The Kalari grounds are usually situated

near a temple, and the pupils, after having touched the feet of the master,

salute the ancestors and bow down to the Goddess, begin the lesson. Kalari

trainings have been codified for over 3000 years and nothing much has changed. The

warming up is essential and demands great suppleness. Each movement is repeated

several times, facing north, east, south and west, till perfect loosening is

achieved. The young pupils pass on to the handling of weapons, starting with the

“Silambam”, a short stick made of extremely hard wood, which in the olden times could

effectively deal with swords. The blows are hard and the parade must be fast and

precise, to avoid being hit on the fingers! They continue with the swords,

heavy, and dangerous, even though they are not sharpened any more, as they are

used. Without guard or any kind of body protection; they whirl, jump and parry,

in an impressive ballet. Young, fearless girls fight with enormous knives,

bigger than their arms and the clash of irons is echoed in the ground. The

session ends with the big canes, favorite weapons of the Buddhist traveler

monks, which they used during their long journey towards China to scare away

attackers. Kalaripayattu,

literally “the way of the battlefield,” still survives in Kerala,

where it is often dedicated to Mahakali. The Kalari grounds are usually situated

near a temple, and the pupils, after having touched the feet of the master,

salute the ancestors and bow down to the Goddess, begin the lesson. Kalari

trainings have been codified for over 3000 years and nothing much has changed. The

warming up is essential and demands great suppleness. Each movement is repeated

several times, facing north, east, south and west, till perfect loosening is

achieved. The young pupils pass on to the handling of weapons, starting with the

“Silambam”, a short stick made of extremely hard wood, which in the olden times could

effectively deal with swords. The blows are hard and the parade must be fast and

precise, to avoid being hit on the fingers! They continue with the swords,